A way of handling dependencies in large-scale Flutter projects¶

Remark: Even though flutter has been the featured framework here, the same solution can easily be recreated in other technologies as there is absolutely no language- or framework-specific code.

The Problem¶

There are many ways in which one can manage dependencies. Some are better at certain things, like ensuring safety and expandability of a project, while others aim at different goals, for example absolute java-script-like freedom. Working on a big, long-lasting, monolithic project comes with its challenges:

1 People¶

The project will be developed by many different people with varying experience levels, from innocent newcomers to living relics. We want to standardize things as much as possible in order to make them simple and easily expandable.

2 Time¶

The project will be worked on over a long period of time - initial code founders might be long gone by the time current hands touch it. We want the structure to guide future masons and support itself as much as possible.

3 Business Pressures¶

The project will go through cycles of different development intensity. Sometimes there are deadlines around every corner, and other times there is room to breathe. We want something that can be safely, and easily, applied during the doom days when "heads run hot."

4 Changes¶

The project will undergo many smaller and bigger changes, even huge ones. It is therefore crucial to use something that will attempt to prevent as many accidental errors as possible.

¶

The solution described in this article aims at solving these problems. We want to ensure as wide testability as possible, and also nudge developers towards specific code decisions to encourage uniformity and other clean code practices.

The presented idea has been in use in our biggest mobile app (Coop medlem ⧉) for over 1.5 years now, as of the end of 2025, and we have been very satisfied with in.

Sample Code¶

The sample code isn't a working code, and it might not make sense (partially or fully). It's been created just to provide an example of implementing the proposed solution, and "test" it against a few real life situations.

Taking Advantage Of Static Analysis¶

Static analysis is an amazing tool; there are probably countless places where one can read about its benefits, so we won't focus on that.

The solution has been structured in such a way that:

- it doesn't allow for runtime registration problems - not having something registered by the time it is retrieved;

- it doesn't allow for runtime type problems - two objects of the same type overriding each other;

Possible problems:

class Dependencies {

final List<Object> _dependencies = [];

void register(Object object) {

_dependencies.add(object);

}

void registerAsync(Future<Object> futureObject) {

futureObject.then(register);

}

T get<T>() {

return _dependencies.whereType().first;

}

}

class AuthModel {}

class FileStorage {

const FileStorage._(this.path);

final String path;

static Future<FileStorage> build(String path) async {

// Do some async work.

return FileStorage._(path);

}

}

void main() {

// Register.

final Dependencies dependencies = Dependencies();

dependencies.registerAsync(FileStorage.build('verbose.log'));

dependencies.registerAsync(FileStorage.build('error.log'));

// 10k lines later in a completely different part of the code.

// We don't know whether this is ready to return, and which instance it will return.

final FileStorage unknownFileStorage = dependencies.get();

// Trying to retrieve something that hasn't been registered.

final AuthModel authModel = dependencies.get();

}

The flexibility and genericness of this solution introduces the two above-mentioned problems, while they can be easily avoided:

class Deps {

const Deps({

required this.errorFileStorage,

required this.verboseFileStorage,

});

final FileStorage verboseFileStorage;

final FileStorage errorFileStorage;

}

class AuthModel {}

class FileStorage {

const FileStorage._(this.path);

final String path;

static Future<FileStorage> build(String path) async {

// Do some async work.

return FileStorage._(path);

}

}

Future<void> main() async {

// Register.

final Deps deps = Deps(

// Having them as FutureOr is also AN option (not the best one).

errorFileStorage: await FileStorage.build('error.log'),

verboseFileStorage: await FileStorage.build('verbose.log'),

);

// 10k lines later in a completely different part of the code.

final FileStorage errorFileStorage = deps.errorFileStorage;

final FileStorage verboseFileStorage = deps.verboseFileStorage;

// We are unable to retrieve something that hasn't been registered.

// final AuthModel authModel = deps.;

}

With this structure we are enforcing/enabling getting specific instance of the

FileStorage, as well as making sure that it is impossible to retrieve

something that hasn't been registered yet.

(We would encourage hiding the async within the storage’s logic and making its

creation synchronous.)

Some might argue that these are trivial human-made errors, while probably mentioning "skill-issue" along the way, and they would be absolutely correct; but, the point of good architecture is to optimize the whole development process and not to address non-human errors (99% of modern software errors are human errors).

Hierarchy¶

Throughout your programming journey you will most likely encounter absolute spaghetti code with complete lack of modularity. It is easy to accidentally end up with such unmaintainable codebase due to all business pressures, lack of experience, laziness, and/or many other reasons. Such code is an absolute pain to deal with, it takes its emotional toll on us programmers, and costs huge amounts of money due to easiness of introducing bugs, delayed feature releases, turnover of employees, etc.

Better responsibility splits can be achieved/encouraged/enforced/nudged (choose your own narrative) with several "mechanisms." Here we would like to emphasize two that can be controlled from the dependencies' perspective. First one aims at putting things at correct layer, and thus, amongst others, avoiding duplication of code, and second one helps with modularity of a layer.

1 Limiting Access To Components¶

In order to improve "clean"-liness of our code it is important to put things in layers that they belong to.

Imagine we have a feature that requires us to make an HTTP call, and then display the data (in several places!). We don't want to end up with the HTTP calls inside the UI layer, and/or the ViewModel (given MVVM architecture), because that makes the layers more complex and introduces a lot of repetition. The way to go would be to have a separate logic layer, that would be responsible for the calls and abstraction of data, and just reference it in UI layer/elements.

In order to encourage this split of responsibilities, we can simply not let some parts of our code, in this case UI, to know about other parts, in this case the HTTP. This can easily be achieved by abstraction of a feature and separation of its creation from its consumption, thus providing access only to the feature abstraction and not its internals.

To address this problem, prefer:

late Dependencies dependencies;

class Dependencies {

Dependencies(this.featureA);

final FeatureA featureA;

// Do NOT provide further.

// final Http http;

}

class FeatureA {

const FeatureA(this._http);

final Http _http;

void doFeature() {}

}

class Http {

void request() {}

}

void main() {

final Http http = Http();

final FeatureA featureA = FeatureA(http);

dependencies = Dependencies(featureA);

doApp();

}

void doApp() {

// Some other part of the app utilizing the feature.

// It has to use the abstraction.

dependencies.featureA.doFeature();

}

over:

late Dependencies dependencies;

class Dependencies {

Dependencies(this.featureA, this.http);

final FeatureA featureA;

final Http http;

}

class FeatureA {

const FeatureA(this.http);

final Http http;

void doFeature() {}

}

class Http {

void request() {}

}

void main() {

final Http http = Http();

final FeatureA featureA = FeatureA(http);

dependencies = Dependencies(featureA, http);

doApp();

}

void doApp() {

// Some other part of the app doing the feature work.

// It can do things on its own.

dependencies.http.request();

}

2 Removing circular dependencies¶

The biggest enemies of understandable code are most often circular dependencies. It is kind of an extension of the previous problem, because it can only be created by providing bigger access to things than required. Fortunately, we can easily eliminate the problem by making injections required at the moment of creation (we can enforce that by not creating easily reachable global variables). This results in much more structured code with bigger modularity, better readability, and many other clean code benefits.

It is hard to give a good code sample of the problems resulting from lack of

structure, as they arise with the mass of a project; but, you can probably

imagine an AuthModel that pokes ProfileModel, which in turn listens to

AuthModel 's stream and does its (now duplicated) actions based on that. It

would be much simpler (better) to have the AuthModel serving at a different

level than the ProfileModel, thus not allowing the auth to know about the

profile, and preventing problems of this nature.

One other benefit of clear hierarchy of components, thus their responsibilities, is that it makes the whole project incomparably more accessible to newcomers (of all experience levels); all it takes is one look at the dependencies that have been declared by (/injected into) a component, and we can know things that would otherwise require scanning all lines of the component (which possibly includes more than one layer of code).

The general idea would be to prefer this:

class Dependencies {

const Dependencies(this.a, this.b, this.c);

final A a;

final B b;

final C c;

}

class A {

A(this.b);

final B b;

void doA() {

b.doB();

// Do A.

}

}

class B {

void doB() {

// Do B.

}

}

class C {

const C(this.a);

final A a;

void doC() {

a.doA();

// Do C.

}

}

void main() {

// We have clearly defined the order of things.

final B b = B();

final A a = A(b);

final C c = C(a);

final Dependencies dependencies = Dependencies(a, b, c);

dependencies.c.doC();

}

over this:

late Dependencies dependencies;

class Dependencies {

const Dependencies(this.a, this.b);

final A a;

final B b;

}

class A {

void doA() {

dependencies.b.doB();

// Do A.

}

}

class B {

void doB() {

// Do B.

}

void doC() {

dependencies.a.doA();

// Do C.

}

}

void main() {

// We don't know if A comes before B or not.

dependencies = Dependencies(A(), B());

dependencies.b.doC();

}

⚠️ Dependency drilling¶

An important note here: nothing is perfect, and this way of injecting can

introduce the problem of dependency drilling. We definitely don't want to

manually pass dependencies through all the layers between the main and our

UI layers. According to us, it is best to pass dependencies through constructor

into the non-UI layers, which often are very predictable in structure, and

then use some context trickery to provide them to the UI layers, which often

end up being endless trees with different number of layers in each branch.

(You can see this being reflected in the example project.)

Testability¶

The main purpose of this solution has been to enable as vast testing as possible.

With modern approach to UI, where design changes are more frequent than sun in Northern Europe, it's extremely expensive to maintain proper suits of UI, or full app-level integration, tests; they are time-consuming to write, and we multiply the costs by making them obsolete so often. In our opinion these things are best left to manual testing in the vast majority of companies.

If an app is coded properly, they are also of lesser significance as logic (non-UI) layers take all crucial, from business perspective, responsibilities, and also shape the UI code by providing more robust data, for example through well-designed abstractions (like sealed error classes) and interfaces (like enforcing getting data from streams) amongst others.

With so much responsibility, for the whole project/company, lying on the shoulders of our logic layers, we think it's crucial to provide as much possibility for testing them as possible.

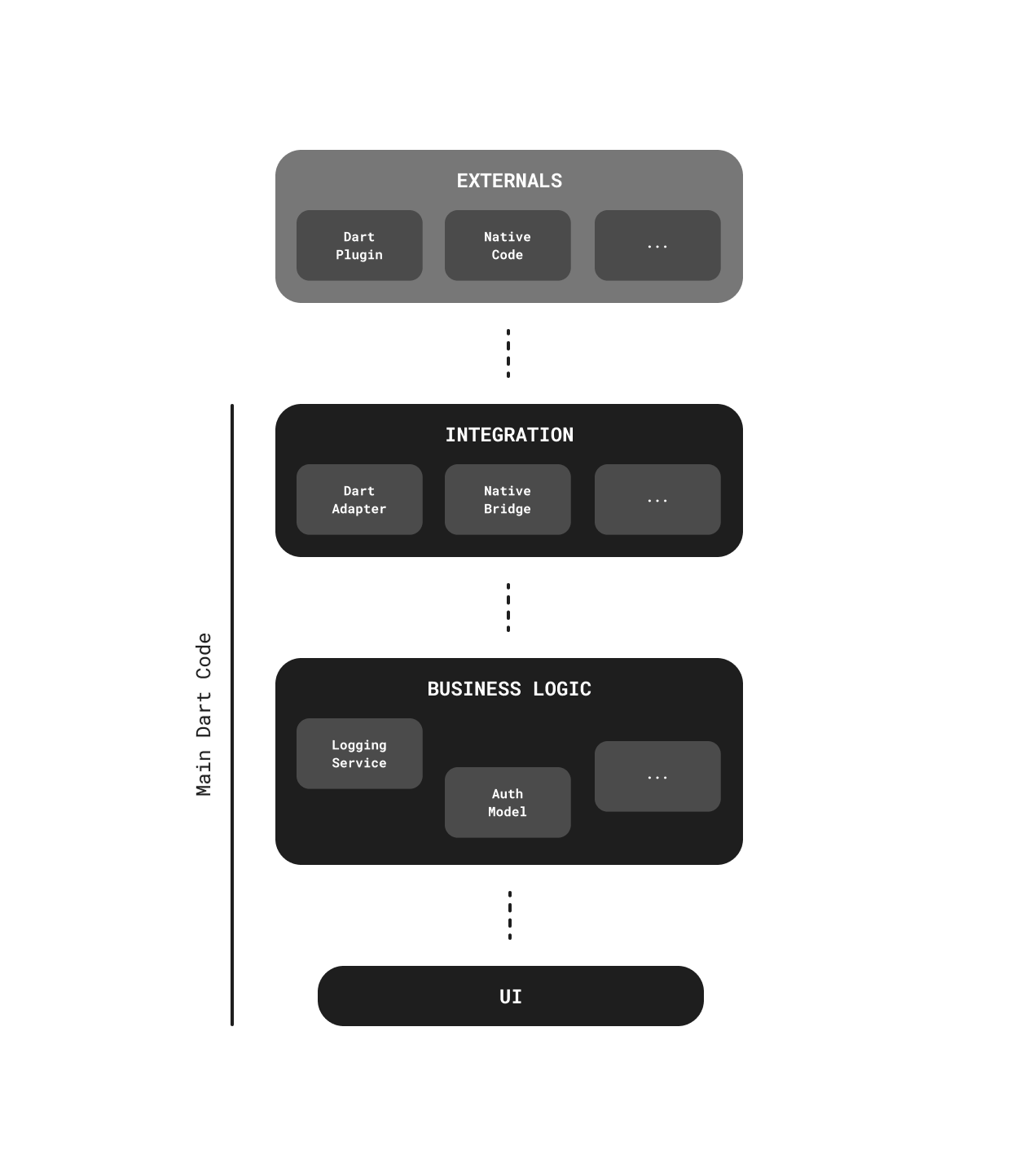

The unremovable part of the solution is the separation of at least two kinds of dependencies:

- the internal dart ones, the code that we fully control (from the project's main dart perspective);

- everything else, which includes external dart libraries as well as our own native code;

We will reference the "everything else" as an integration layer. These are the things that we do not control through the main dart code, and thus cannot be easily (code) tested.

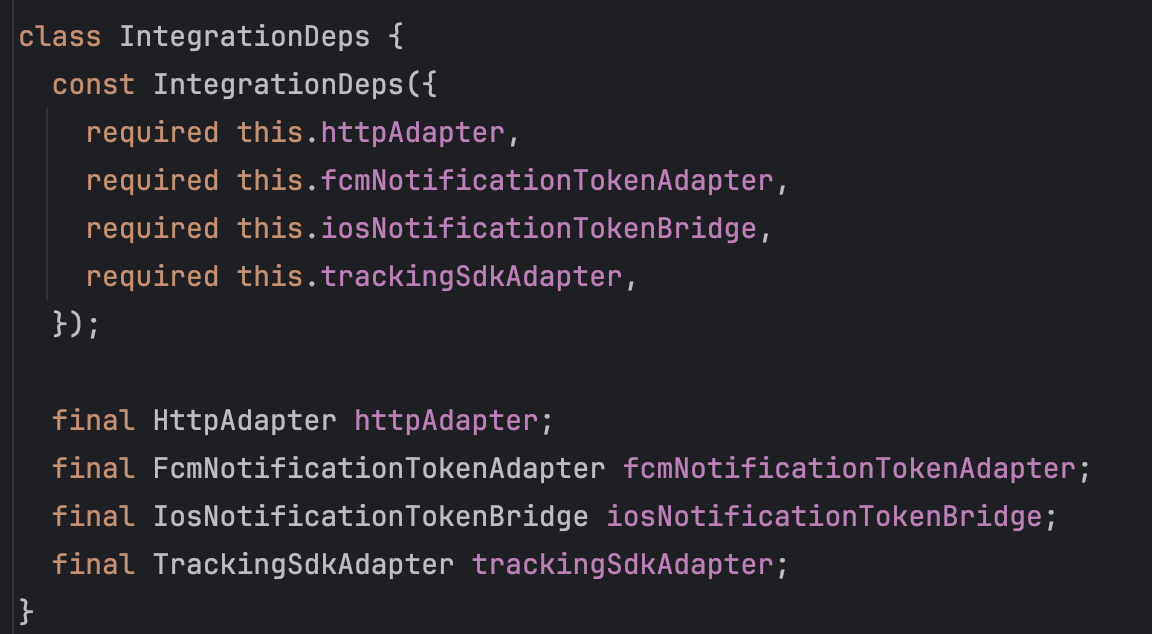

example of what your integration layer might look like

example of what your integration layer might look like

Integration And Other Layers¶

For the code that we don't control, we assume that whoever controls it has done his part of ensuring proper functioning, and we focus on our own doings. Thus, the integration layer is an extremely shallow and simple one; all it does is basically adapting the externals so that they follow our designs, so that, in turn, we can easily mock everything.

There should be as little logic as possible, to the point of there being at most some data mappings (from our experience even innocently looking singular ifs can cause bugs, and, if put in this layer, they become untestable).

So we have this integration layer, that acts like an adapter to our code, and then we have the rest of our logic. With this we can separate building of the integration so that it's different between working code and our test environment.

While doing this, it's beneficial to make every new addition to the integration layer require additions to all supported environments. From experience, we know that due to different reasons it's often tempting to skip adding support for the testing environment, or other less used environments that you might have, and after some time of such disuse they become extremely expensive to bring back to life.

With such setup we can test literally all workings of the app (without the need for any UI). This enables us to do many wonderful things, that are otherwise impossible to check, like:

- testing concurrent work due to spawning second Isolate (process);

- ensuring that all initializations are complete before logic gets executed;

- ensuring that all necessary interceptors are attached before first request is sent;

- lots of deadlock testing, if we are making extensive use of the event loop and other mechanisms;

- ...

@isTest

void allDepsTest({

required String description,

required AllDepsTestCallback testFun,

SupportedPlatform supportedPlatform = SupportedPlatform.android,

MockIntegrationDeps? mockIntegrationDeps,

}) {

test(

description,

() async {

final MockIntegrationDeps finalMockIntegrationDeps = mockIntegrationDeps ?? MockIntegrationDeps();

final DepsFactory factory = DepsFactory(

integrationDepsFactory: _MockIntegrationDepsFactory(

mockIntegrationDeps: finalMockIntegrationDeps,

),

);

final AppDeps appDeps = factory.build(

supportedPlatform: supportedPlatform,

);

await testFun.call(appDeps, finalMockIntegrationDeps);

},

);

}

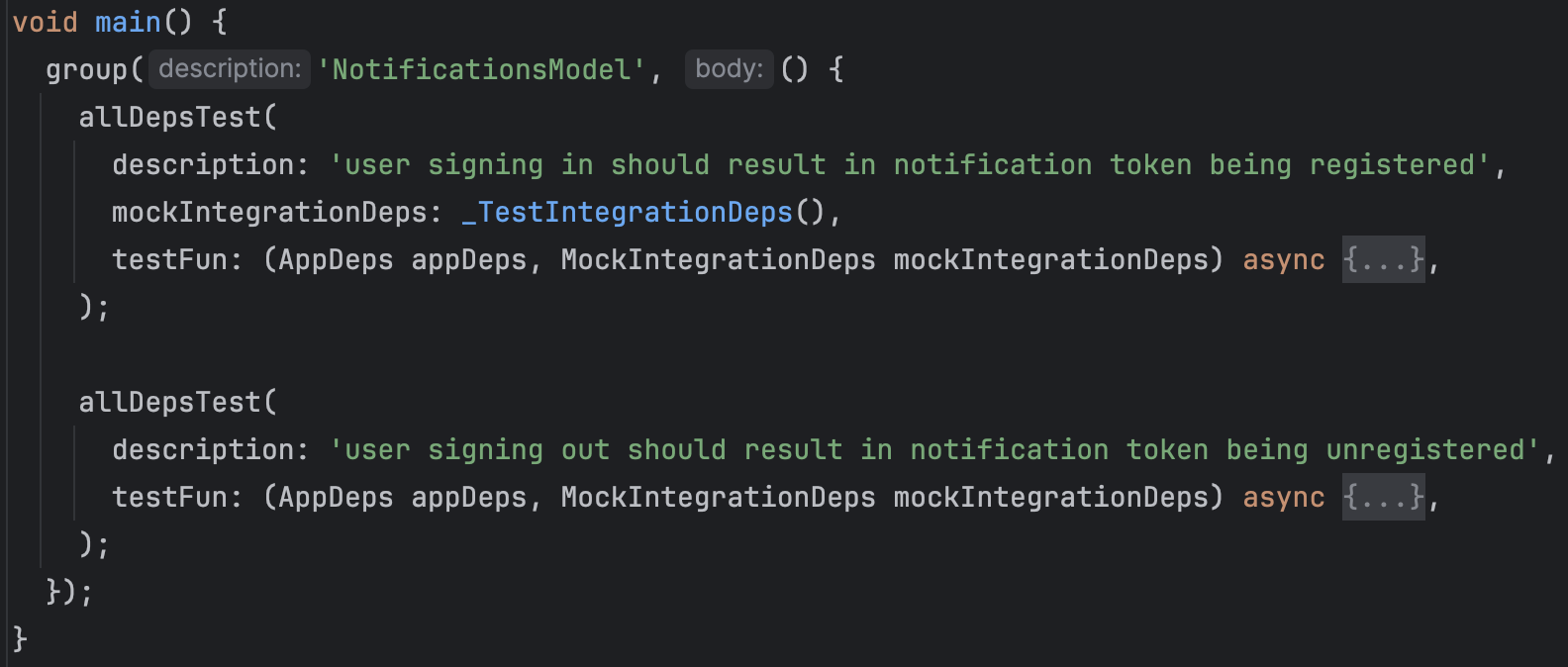

We are running almost the whole app, with no UI and with mocked externals, and thus can do all sorts of logic integration tests with minimal effort (given proper mocks). All sorts of in-app logic tests, like simulating users signing in and checking if all automatic fetches are executed, as well as calls to external entities, for example whether correct external vendor has been poked, can be created.

Other real-life tests, that we have produced due to production bugs, include:

- testing if a link trigger, resulting from user tap action, gets a session transfer token attached (if it goes to our internal domains);

- ensuring that notification token gets registered as soon as user signs in, but also unregistered as soon as he signs out. Seems trivial, but one action requires auth token being present, and the other happens when the auth token is no longer available, so we have to ensure that we use correct HTTP logic throughout the whole process, which is hidden inside a completely different layer;

- our

ProfileModelis the most crucial model (MVVM) on which the rest of the app relies. Things like: optimized methods terminating before the model's state has been fully updated, have caused us enormous troubles in many different semi-random parts of the app. Thus, we have many tests checking if the model's actions are fully aligned with its state. - (The complexity of this model makes it rather hard to create completely separate model tests, and being able to “simply” run the whole app helped a lot.)

...and many others.

⚠️ Appropriate testing level¶

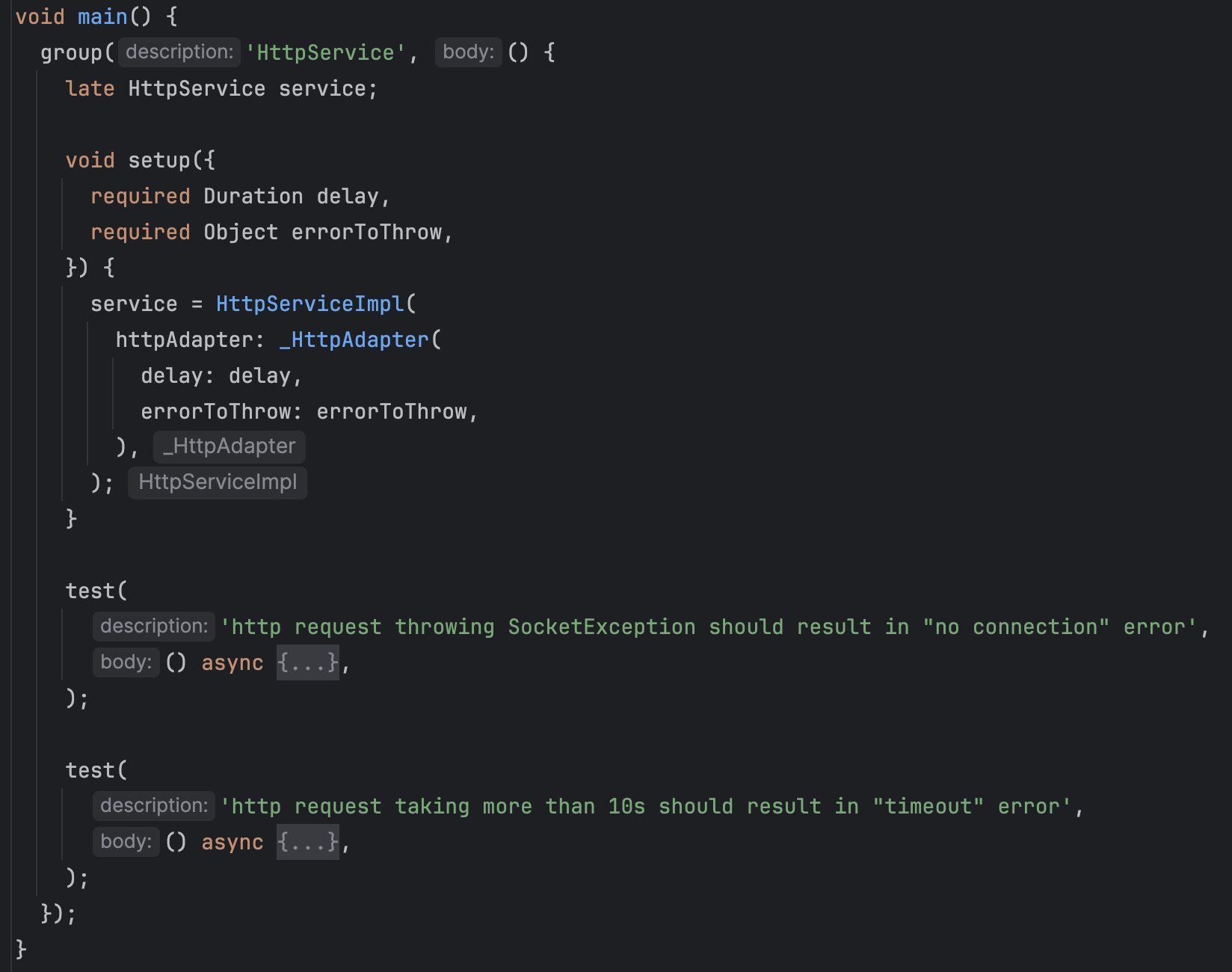

We also find it important to mention that these "full app" tests are not an answer to everything. Sometimes singular mocking might be more difficult than running the whole thing, for example if there are many setup steps that we would have to duplicate in tests, or, as mentioned, things require complexity of the whole app to cause problems or be testable. Many other times, most in fact, it is however preferable to do smaller component/feature tests. They often, but not always, are cheaper to maintain, especially if we are testing 200 different scenarios.

example of tests that benefits from narrower scope with more mocking possibilities

example of tests that benefits from narrower scope with more mocking possibilities

example of tests that require wider scope

example of tests that require wider scope

Customization¶

As we have mentioned, there are at least two layers (integration and the rest) needed in order to get the benefit of vast testability. You can however easily add more layers or create higher strictness with imaginative interfaces.

We can imagine projects that require some things to be created before authentication code, and then some afterwards. Or you might want to separate a layer for things that are your coded inside the project, but are not project-specific. Each project has its own requirements and problems, therefore we encourage you (the realm’s expert), to adjust it to the needs.

You might even have a need, as we do, to create two separate sets of

dependencies. One that are created for the main app process, and one for

handling notifications in a background

Isolete ⧉. This way we are not

initializing more than needed for the background process (and ensure that

things don’t end up in it by simple accident).

// You can define things however you want.

class AppDeps {

AppDeps({

required this.serviceDeps,

required this.modelDeps,

});

final ServiceDeps serviceDeps;

final ModelDeps modelDeps;

}

// "All" - for the main process.

class AllDeps {

AllDeps({

required this.integrationDeps,

required this.serviceDeps,

required this.modelDeps,

});

final IntegrationDeps integrationDeps;

final ServiceDeps serviceDeps;

final ModelDeps modelDeps;

}

class BackgroundNotificationDeps {

BackgroundNotificationDeps({

required this.localNotificationsService,

required this.authModel,

});

final LocalNotificationsService localNotificationsService;

final AuthModel authModel;

}

The solution brings a need for small bits of extra code, compared to some absolutely minimal setups, but we believe the benefits are well worth it.

Final Words¶

There is no “one thing” that will fit all requirements. The actual code used in the before-mentioned app differs ever-so-slightly from the one presented here. Abstraction layers can be added and/or removed to suit your particular needs, and things can be moved around. We found the current flutter "standards" (namely GetIt) not fulfilling our needs and desires, mainly when it comes to easiness of maintaining big suits of tests and standardizing hierarchy of components, and thus this dependency structure has been born.